Traditions & Culture of Collecting Articles by and about Collectors, Librarians, and Booksellers

This Catalogue and its Predecessors Jeremy M. Norman

Originally published as an introduction to The Haskell F. Norman Library of Science & Medicine (1991)

This catalogue is intended both as a record of the library collected by my father, Haskell F. Norman, and as a detailed bibliographical guide to many first editions of classics of science and medicine for collectors, librarians, and booksellers. While numerous individual authors and scientific and medical subjects represented in this catalogue have previously received detailed bibliographical treatment, this is the first catalogue to provide complete annotated descriptions, with full collations, paginations, and plate counts, for a very wide range of the classics in the history of science and medicine from the fifteenth to twentieth centuries.

In preparing our descriptions we paid special attention to bibliographical variants and states, in some cases indicating useful issue points and variants whether or not these variants are included in the library. Because this library contains so many presentation copies, and other unique association copies, including works in remarkable bindings, we also paid special attention to provenance throughout the catalogue, recognizing, however, that time did not permit the reconstruction of more complete provenance records for 2,600 items acquired over forty years. Under the provenance heading we decided to include the names of the booksellers from whom each work was purchased, when this information was available. We were unable to provide acquisition dates because the original invoices were not preserved.

Within the scope of our descriptions we also attempted to provide information concerning the publishing history of particular works, especially if this might shed some light on how a book was originally issued, such as in fascicles by subscription, or if it might help to account for bibliographical variants. We also attempted to determine edition size in the few cases where this was possible. Information of this type is very difficult to obtain and that which we have published was chiefly gleaned from a careful examination of secondary sources. Sometimes our experience in handling different copies of the same work over twenty-five years enabled us to make original observations; see for example our descriptions of Cruveilhier (no. 538) or Vicq d’Azyr (no. 2150). However, we were also fortunate in having access to photocopies of relevant portions of the publishing ledgers of Longman & Co. at the University of Reading, from which we were able to establish the edition sizes of a few medical books published in England during the nineteenth century. From the very limited information available one might observe that authors of esoteric scientific and medical works were not infrequently called upon to finance their own publications, (see, for example, nos. 341 and 2255) and that the edition sizes were sometimes smaller than one might have imagined, typically under 1,000 copies and frequently less than 500 (see nos. 466, 872 and 2064). Of course some editions were significantly larger. A detailed break-down of the expenses in publishing a scientific book in the early nineteenth century appeared on pp. 166-67 of Charles Babbage’s On the Economy of Machinery and Manufactures (nos. 92 & 93) in which he utilized the costs in publishing 3000 copies of that particular work as “an example of the costs of the different processes of manufacture”. Babbage’s analysis did not include the costs of the large-paper copies for presentation to his friends and patrons, costs for which presumably he was responsible. This work was an outstanding commercial success with the entire first edition sold within two months. Another commercial success was the first edition of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (no. 593). In fact the printing of the first edition of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (no. 593), The first edition, widely known to have been 1,250 copies, may well have been above average then for a scientific work, taking into account the relatively small number of scientifically educated members of Victorian society. Remarkably, the first edition was oversubscribed to booksellers by 250 copies on 24 November 1859, its first day of publication, but instead of reprinting immediately, Darwin’s publisher, John Murray, asked him to revise the work, and a corrected second edition of 3,000 copies was issued on 7 January 1860. What would be the first printing a similar “blockbuster” scientific work if it were published with effective promotion today?

As professional users of bibliographies, we have planned this work for maximum ease of use. Thus all books have been are arranged in one alphabetical sequence by author’s last name, except for the very extensive collections of the writings of Sigmund Freud and on Mesmer and Mesmerism. These last are catalogued in separate chapters at the end of the main catalogue, and are separately numbered with the letters F and M prefixing their respective individual entry numbers. This book has been designed both for elegance and legibility. The entry numbers, by which the items are indexed, have been made particularly easy to read. For convenient access to the wide range of information in the catalogue there are comprehensive indices to authors, subjects, artists, binders, and provenance.

In her introduction Diana Hook has described the cataloguing methodology she developed for this project. Having completed this catalogue with Diana after seven years of almost continuous labor, during which we would often wonder when this seemingly interminable task might ever end (especially as Dad continued to add significant volumes almost right up to the time of printing), I find myself asking where the catalogue fits in the history of the catalogues of private, as distinct from institutional, scientific and medical book collections, and of the history of private collecting in these fields. What follows is an attempt to answer those questions. For the purposes of this essay I am making several exclusions: First, I am excluding the great encyclopedic libraries of the past, which invariably contained some scientific and medical books, unless the libraries were formed by physicians or scientists. Thus I am excluding libraries such as those formed by Jacques-Auguste de Thou and his son, even though scientific books from that library are catalogued here (nos. 1216, 2212 and 2222). Similarly, I am excluding the library of Louis XIV’s finance minister, Jean Baptiste Colbert (no. 1049) and that of his immediate predecessor, Nicolas Fouquet (no. 2038). However, I am including large libraries of many early physicians even if only a portion of these libraries included medicine or science. I am also excluding the many private libraries of natural history books, especially descriptive color plate books per se, from my definition of scientific books, since the Norman library contains relatively few books of this type, and they represent a different tradition in book collecting. Like many subjects in the history of collecting, the history of collecting scientific and medical books has been studied less thoroughly than might be desired. The account that follows does not pretend to be the serious history that is needed; however, I hope that it summarizes some available information and points the way for future research. Whenever possible in this account I will emphasize collectors that are represented in the Norman library either by actual books they owned or by books they wrote. My main effort will be to outline the development of this field of collecting prior to Sir William Osler (1849-1919) who remains the watershed figure in the history of this field. After Osler it is possible to trace an uninterrupted chain of private collectors of books in the history of science and medicine right up to the present day. Before Osler the record is far less complete; nevertheless considerable information is available, from which I have made selections. The major sources of additional information are either cited in the text of this essay or in the footnotes. In discussing twentieth century collectors after Osler I will limit my remarks to those whose catalogues or reference works which were influential in the formation of this library.

Before the second half of the nineteenth century, when the first bibliographical catalogues of the private libraries of collectors of scientific books were published, records of private collections of this type existed, with a few notable exceptions, chiefly in library sales records. Pollard and Ehrman1G. Pollard & A. Ehrman, The Distribution of Books by Catalogue from the Invention of Printing to A.D. 1800, Based on Material in The Broxbourne Library (Cambridge: Printed for presentation to members of The Roxburghe Club, 1965). Another related reference work I found useful in this project was the second edition of Archer Taylor’s Book Catalogues, Their Varieties and Uses, revised by Wm. P. Barlow, Jr. (New York: Frederic C. Beil, 1987). Those who wish to research catalogues of collectors such as Colbert or the de Thou family should begin with Taylor’s work. provide an excellent discussion of the three types of sale catalogues: auction sales, inventory sales in which the books are individually listed but not priced, and book dealers’ catalogues, usually with prices listed. Since book auctions did not become popular until the second half of the seventeenth century, and the few extant book dealers’ catalogues from this period are relatively uninformative for our purposes, what records we have of medical and scientific libraries before that time come chiefly from manuscript inventories and inventory sale catalogues. Beginning around 1650, using inventory sale catalogues, auction catalogues and the few relevant catalogues of private scientific libraries, we may begin to recontruct some of the outline of the history of collecting antiquarian books in science and medicine.

In her preliminary survey, “Scientists’ libraries: A handlist of printed sources,”2E. B. Wells, “Scientists’ libraries: A handlist of printed sources,” Annals of Science 40 (1983), 317-89. A less comprehensive narrative on the same subject is “Private scientific libraries,” Chap. 10 in the third edition of J. Thornton & R. Tully’s Scientific Books, Libraries and Collectors: A Study of Bibliography and the Book Trade in Relation to Science (London: The Library Association, 1971). Ellen B. Wells listed 1,200 titles from catalogues, essays, and articles concerning the libraries of about 880 scientists, from the earliest available records up to the present. Anyone who wishes to pursue research on this subject beyond what I have done here should begin with Wells’s survey. She observed that of the 880 scientists whose libraries could be documented, 640 were physicians, confirming the active tradition of physicians as book collectors. As a profession, physicians were certainly among the first groups to earn their living from the application of science. They must have needed office libraries as soon as books were available. In considering the early history of the collecting of scientific books it is difficult to confirm whether physicians were buying books strictly for practical use or whether they might also have been acting as book collectors, building a library for its own sake. One criterion that might give us a clue as to their motivation is the number of volumes in these early libraries; another clue is whether or not the libraries contained first editions of classics instead of just editions published during their owner’s lifetime.

Alain Besson has ably summarized the available literature on the history of private medical libraries.3A. Besson, “Private medical libraries.” Chap. 9 in Thornton’s Medical Books, Libraries and Collectors, 3rd ed., edited by A. Besson (Aldershot: Gower Publishing, 1990). Besson based this article on Chap. 10 of the second edition of Thornton’s Medical Books, Libraries and Collectors (London: Andre Deutsch, 1966). I found some useful data in the second edition that was not included in the third. Perhaps the earliest library of any scientist, concerning which we have reliable documentation, is the library of the physician and humanist, Giovanni de Dondi (1330-89), the son of Giacomo de Dondi (1293-1359) who wrote one of the earliest medical dictionaries, Liber aggregationis (no. 649). The inventory of Giovanni de Dondi’s library prepared at his death lists 111 manuscript titles. While this might not seem like an especially significant number of books to us, we must remember that manuscript books were particularly time-consuming to produce and were thus expensive and relatively difficult to obtain.

The limited records of scientific libraries in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, chiefly medical, are summarized by Besson and Wells. It is noteworthy that the physician and theologian Nicolaus Pol (c. 1470-1532) is thought to have collected as many as 1,500 volumes, of which 467 were actually located by Max H. Fisch in 1947.4M. H. Fisch, Nicolaus Pol Doctor 1494… (New York: Herbert Reichner, 1947). Besson also summarizes research on the libraries of various Cambridge physicians of the sixteenth century and of the physician, mathematician and alchemist John Dee (1527-1808), concerning the manuscript inventories of whose library there has been considerable scholarship. It would appear that most of these libraries of books and manuscripts contained fewer than 100 volumes.

From our standpoint a more significant observation might be that the science of bibliography was to a major extent developed in its early years by physicians, including Conrad Gesner (1516-1565). Gesner’s Bibliotheca universalis (1545) is considered by Breslauer and Folter “the first ’universal bibliography’, that is, an international bibliography of authors who wrote in the learned languages, alphabetically arranged by their first names in accordance with medieval usage. Short biographical data precede the lists of works, indications of printing places and dates, printers and editors, where applicable. About 12,000 titles are listed, an amazing achievement, especially in consideration of the author’s age, twenty-nine at the time of publication.”5B. H. Breslauer & R. Folter, Bibliography, its History and Development (New York, The Grolier Club, 1984), p.39. Gesner’s work is cited as item no. 14 in this exhibition catalogue. Another work which should be consulted on this topic is T. Besterman, The Beginnings of Systematic Bibliography, 2nd ed. (London, 1940). Gesner personally collected a substantial library, a catalogue of which was published as Bibliotheca instituta et collecta primum a Conrado Gesner … in vera postremo recognita … per Josiam Simlerum … (Zurich, 1574). Gesner may have begun the tradition of the physician as bibliographer, both in medicine, and on learned subjects generally, which persisted through the eighteenth century.6John F. Fulton, The Great Medical Bibliographers: A Study in Humanism (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1951). In fact so many of the early pioneers of bibliography were physicians that the early parts of Fulton’s account is a kind of sketch of the history of bibliography in general.

By the seventeenth century it is thought that a wide variety of physicians possessed private libraries but that these libraries were usually dispersed with their belongings, leaving no record of their library holdings. William Harvey (1578-1657; nos. 1006-1012) built a library and museum for the Royal College of Physicians, to which he also bequeathed his books and papers. Regrettably, almost his entire library was destroyed during the Civil War and the Great Fire of 1666. Today only a handful of books from his library are known.

Probably the earliest catalogue of a private scientific library, certainly the earliest bibliography of chemistry, and apparently the earliest specialized scientific, as distinct from medical, bibliography of any kind was the Bibliotheca chimica (Paris, 1654) of Pierre Borel (see no. 268). A physician and scientist of wide interests, Borel collected a library of 4,000 books and manuscripts on alchemy and chemistry. His library was more than a working collection as Borel included fifteenth century books and unique manuscripts.7Breslauer & Folter, no. 59.

One of the great libraries of the seventeenth century, for which a manuscript inventory is preserved in La Bibliothèque Inguimbertine de Carpentras, is that of the politician, astronomer and patron of science, Nicholas Claude Fabri de Peiresc (1580-1673). Although none of Peiresc’s works were published during his lifetime, he left very extensive correspondence and a large collection of manuscripts which are preserved in several French libraries. A wide-ranging collector of coins and medals, fossils and crystals as well as books, Peiresc also maintained at his home in Provence the third largest garden in France. His library is thought to have included 5,000 books on a very wide range of subjects, as well as approximately two hundred ancient and medieval manuscripts.8The most recent and extensively illustrated account of Peiresc’s life and works is J. Hellin’s Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc 1580-1637 (Brussels: Raymond Lielens, 1980). An account of Peiresc’s scientific work appears in the Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Perhaps because he left so many unpublished manuscripts and letters, Peiresc was the subject of a surprisingly large amount of scholarship, particularly in France during the nineteenth century. Many of Peiresc’s books are notable for their bindings, typically in crimson morocco, by his house binder Simon Corbéran. The Norman library includes a particularly fine example-- Peiresc’s copy of Ramelli (no. 1777).

The earliest sale catalogue of a private scientific library may be that of Peiresc’s contemporary, the physician, Jean Riolan the Younger (1580-1657) who is most often recalled today as an opponent of Harvey’s theories of the circulation (see no. 1010). The neurophysiologist, bibliographer and book collector John F. Fulton (1899-1960) owned a possibly unique copy of an inventory sale catalogue of Riolan’s library issued by the Parisian booksellers Simeon Piget and Federicus Leonard in 1664.9Fulton, Medical Bibliographers, pp. 27-28. The library must have been purchased outright by John Martyn and James Allestrye, booksellers for the Royal Society, in St. Paul’s Churchyard, London, as they issued another inventory sale catalogue of the complete library in 1665. Fulton observes that neither of the Riolan catalogues include prices and tentatively concludes that the books were disposed of to the highest offer through private negotiation.

In selling the Riolan library Martyn and Allestrye were filling a demand in England for continental scientific and medical books. Robert Scott, bookseller to Charles ii and considered “in his time the greatest librarian in Europe,”10Quoted in Breslauer & Folter, no. 71. also specialized in imported books. His Catalogus librorum ex variis Europae partibus advectorum (London, 1674) is considered the most important bookseller’s catalogue published in England up to that time. The catalogue covered virtually all most major subjects, and is notable for listing a large number of sixteenth-century books along with volumes published in the mid-seventeenth century. Among medical books, Scott included the second edition of Vesalius (1555); in astronomy he listed the second edition of Copernicus (1566). Fifteenth-century books do not appear in Scott’s catalogue, so it is reasonable to conclude that he was not deliberately intending to carry antiquarian goods. Most likely he was listing books for which he received consistent demand.

During the second half of the seventeenth century interest in antiquarian books was stimulated by the development of book auctions. The first book auction, a sale conducted by Louis Elzevier, took place in Leiden in 1596.11The best account of the early development of book auctions is in Pollard & Ehrmann, Distribution of Books. The practice became increasingly popular in Holland but only gradually spread to other countries, with the first English book auction occurring in London in 1676. As is still often the case today, auction catalogues constitute the only record of many early libraries. The most extensive library to be sold at auction in England during the seventeenth century was that of Francis Bernard (1627-98), physician to St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, and physician to James I, whose immense private library of “14,747 works and 39 bundles” included 4,484 volumes on medicine. Bernard’s motivations in collecting such a large library certainly went beyond scholarship in its strictest sense, but as if there was something wrong about collecting books for their own sake, or perhaps because Bernard did not favor fine copies, the auctioneers prefaced their catalogue with the following remarks:

“We must confess that being a Person who Collected his Books for use, and not for ostentation or ornament, he seem’d no more solicitous about their Dress than his own; and therefore you’ll find that a gilt Back or a large Margin was very seldom any inducement to him to buy.”12Quoted in Besson, p. 274.

The Norman copy of the second edition of Cesalpino (no. 431) most probably came from Francis Bernard’s library, which was dispersed in 1698.

A contemporary of Bernard, and one of the first men known to have made his living strictly through the practice of science as distinct from medicine, was Robert Hooke (1635-1702; see nos. 1092-1102). Beginning his scientific career as Robert Boyle’s assistant, Hooke became the official “experimenter” for the nascent Royal Society, the first Cutlerian Lecturer on mechanics, and professor of geometry at Gresham College in London. However, he made most of his money as “surveyor” of London after the Great Fire of 1666. In this capacity Hooke also served as architect for a number of important London buildings. Hooke was a passionate book collector and book auction buff who sometimes attended as many as four book auctions in one day. He built up a library of 3,000 volumes and we are fortunate in that Hooke recorded in his diary numerous purchases of books, either from booksellers or at auction. A detailed account of Hooke’s book-buying activities, together with a reprint of the 1702 auction catalogue of his library, has been published by Leona Rostenberg.13L. Rostenberg, The Library of Robert Hooke: The Scientific Book Trade of Restoration England (Santa Monica, CA: Modoc Press, 1989). While much of Hooke’s collection would be considered more a working library than a collection of antiquarian books, he did have among his approximately 900 volumes of scientific books, including 27 editions of Euclid—far more than could have ever been practically useful.

Scott’s offering of medical books in 1674 included several classics well known today. The books do not appear to be listed in any discernable order.

Scott’s offering of medical books in 1674 included several classics well known today. The books do not appear to be listed in any discernable order.As part of the extensive scholarship on Sir Isaac Newton, the catalogue of his library was published three times, most definitively by John Harrison in 1978.14J. Harrison, The Library of Isaac Newton (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978). Newton died intestate, and his library of “362 books in folio, 477 in quarto, 1057 in octavo …with above one hundredweight of pamphlets and wast [sic] books” was sold soon after his death for £300 to Johns Huggins, a warden at the Fleet Prison. John Huggins sent the library to his son Charles, then rector of Chinnor, near Oxford. Charles Huggins added his bookplate to each volume, and when he died intestate in 1750 his successor as rector, the Rev. Dr. James Musgrave, purchased the collection for £400, and pasted his book-plate in each volume, frequently over that of Charles Huggins. He also had all the books catalogued and press-marked.

The manuscript catalogue of Musgrave’s collection, prepared around 1760, is still preserved. After Musgrave’s death in 1778 the books were transferred to Barnsley Park where they remained, virtually inaccessable for more than 100 years, and long enough for everyone to forget their famous origin. In 1920 they were sent to Thame Park, whence many were dispersed at an auction in 1920 without any indication that the books had belonged to Sir Isaac Newton. The books fetched a total of only £170 in 1920, less than half of their value in 1750. A number of the books were purchased by Heinrich Zeitlinger and may be found in the Sotheran catalogues. Harrison has documented the history of Newton’s library with great thoroughness.

Newton’s library was unquestionably a working collection rather than a collection of rarities. The sixteenth-century books on alchemy that it contained were used by Newton in his extensive alchemical researches, none of which were published during his lifetime, and many of which still remain in manuscript. The Norman library contains two books that belonged to Newton; both are first editions by his close friend, the philosopher John Locke (nos. 1380 and 1382). Incidentally, Locke, who was by profession a physician, collected a working library of 3,675 volumes, only ten percent of which concerned medicine. He maintained a meticulous library catalogue and his own shelf-mark system. While his library was also dispersed, its nucleus, together with a large collection of his manuscripts and papers, is in the Bodleian Library, Oxford. The catalogue of his library was published by John Harrison and Peter Laslett.15J. Harrison & P. Laslett, The Library of John Locke (Oxford: Oxford Bibliographical Society, 1965).

The question remains whether in the seventeenth century scientists and physicians may have collected early books for their antiquarian value, or practical use, or both. Even though a few men such as Newton, or others represented in the Norman library, made discoveries of the most revolutionary impact, the speed of scientific and medical change in the seventeenth century, compared to the rapid advances of our own time, was extremely slow. It is hard for us to gauge the extent to which seventeenth-century scientists, rooted in tradition, viewed classic works of the past as useful or obsolete. Even if they regarded a work as obsolete, to what extent did they feel it necessary to study the classical works of their predecessors, the works of the “giants” on whose shoulders Newton proclaimed himself to have stood?

Front paste-down of Newton’s copy of Locke’s Essay on Humane Understanding (no. 1380). The Huggins shelf-mark is visible in the upper left corner. The Musgrave bookplate with its motto “Philosophemur” is pasted over that of Huggins. The Musgrave shelf-mark is penned on the bookplate.

Front paste-down of Newton’s copy of Locke’s Essay on Humane Understanding (no. 1380). The Huggins shelf-mark is visible in the upper left corner. The Musgrave bookplate with its motto “Philosophemur” is pasted over that of Huggins. The Musgrave shelf-mark is penned on the bookplate.  Catalogue of the Fratres Horthemels, medical booksellers and publishers, 1730

Catalogue of the Fratres Horthemels, medical booksellers and publishers, 1730

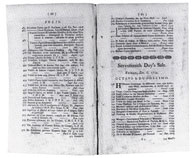

Title and sample page from the auction catalogue of Boerhaave’s library. Following auction tradition, Boerhaave’s books were arranged by subject and then by size within each subject

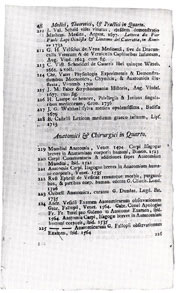

Title and sample page from the auction catalogue of Boerhaave’s library. Following auction tradition, Boerhaave’s books were arranged by subject and then by size within each subject  Folio anatomies from the auction catalogue of Richard Mead’s library included first editions of many works well known today.

Folio anatomies from the auction catalogue of Richard Mead’s library included first editions of many works well known today. A clue to how some sixteenth-century medical books may have been commercially valued by booksellers in the first part of the eighteenth century is offered by the catalogue of the Parisian medical booksellers and publishers Fratres Horthemels, published in partnership with the firm of J.L. Koenig of Offenbach in 1730.16Libri huiusce facultatis medicae venales Parisiis apud Fratres Horthemels propè Domum Sorbonn. nec non Offenbaci ad Moenum apud J.L. Koenig, 1730. See Jeremy Norman & Co., Inc., Catalogue 21, Medicine & the Life Sciences (San Francisco, 1991), no. 431. Throughout this 50-page catalogue the works are priced in German funds, and the factor controlling price seems mainly to be size and number of volumes. Books from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries are offered alongside eighteenth-century volumes with no apparent premium placed on age or rarity. Of course we should not draw any general conclusions from examination of this single dealer catalogue.

A better measure of the market for antiquarian books in science and medicine at this time comes from the superb library of Herman Boerhaave (1668-1738; see nos. 255-257), sold at auction in Leiden by Samuel Luchtmans from 8 June to 16 June 1739.17Copy used is in the author’s collection. Boerhaave’s library contained about 3,300 volumes on a wide range of subjects, including many outstanding illustrated works in botany and fine illustrated works on anatomy. As one would have expected, Boerhaave, the editor of a new edition of the writings of Vesalius (no. 2143), owned a first edition of the Fabrica. What one might not have expected was that he also owned all of the rare first editions of Berengario da Carpi, whose anatomical works prior to Vesalius would certainly have had no practical scientific value by the eighteenth century. Boerhaave also owned a fifteenth-century edition of Mondino, confirming that he was a book collector as well as a scholar. At the end of the catalogue is a group of “Libri Prohibiti” including first editions of Spinoza. Partially because of Boerhaave’s great fame, the sale of his library attracted more than the usual interest; altogether it realized 13,000 guilders.

By the middle of the eighteenth century book auctions were well established in England, and that of the library of the wealthy physician Richard Mead (1673-1754) reflected a notable increase in the prices of collectable books. His library of over 10,000 volumes, including many spectacular collector’s items in the history of anatomy and other subjects in medicine and science, realized over £5,500 in a sale that lasted no fewer than 28 days (nos. 1477-1480). Following the auction tradition, Mead’s catalogues were arranged only in broad subject headings, subdivided by size of the volumes. Mead was also a collector of classical antiquities, paintings, coins, and medals. His art collections, including several Rembrandts, realized £10,550. Mead is represented in the Norman library not only by the auction catalogue of his library and art collections but by items he wrote (nos. 1475-1476) and by the splendid edition of Cowper’s Myotomia reformata (no. 530) that he produced. Some of the magnificent engravings illustrating that work may have reproduced drawings by Rubens and Raphael in Mead’s own collections.

Another stimulus to book collecting, as distinct from accumulation for personal or professional use, was the appearance in the mid-eighteenth century of the first guides for collectors. Petzholdt18J. Petzholdt, Bibliotheca bibliographica (Leipzig, 1866; reprint: Nieuwkoop: De Graaf, 1972). describes several works of this type, including Johannes Vogt’s Catalogus historico-criticus librorum rariorum, some editions of which supposedly included prices, as did other guides which followed. From 1763 to 1782 the bookseller Guillaume de Bure (1731-1782) published what might be the first real book on how to collect books. His seven-volume Bibliographie instructive, with its three supplementary volumes, not only provided collectors with suggestions as to what to collect but also explained how to identify the various editions. Breslauer and Folter consider de Bure “the first in a long tradition of French scholar-booksellers”.19Breslauer & Folter, no. 107.

Through the acquisition of complete libraries, including a significant part of that of Francis Bernard, the wealthy English physician Sir Hans Sloane (1660-1753) was able to accumulate 40,000 printed books and 3,700 manuscripts on virtually every subject, along with antiquities, coins, medals, crystals, seals, gems, botanical and zoological specimens, prints, drawings, and paintings. His library is represented in the Norman library by his copy of Cheselden’s Osteographia (no. 466), and by his copies of vols. 47-53 of the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, of which organization he was secretary from 1693-1712 and president from 1727-1741 (no. 1694). At his death Sloane instructed his executors to offer his entire collections to the English nation for the sum of £20,000. The purchase price was raised by a lottery, and Sloane’s collections became the foundation of the British Museum and the British Library.

The other great scientific book collector of eighteenth century England was the physician and patron of the arts William Hunter (1718-83), represented in the Norman library by his most notable publication, The Anatomy of the Human Gravid Uterus, printed by William Baskerville (no. 1125). Hunter’s library, of which about half was medical, included 534 incunabula and 2,300 sixteenth century books, several printed on vellum. In his will he endowed the Hunterian Museum at the University of Glasgow, to which he bequeathed his library, coin collection, and collection of paintings. Catalogues of his books and of his collection of over 600 volumes of medieval and renaissance manuscripts were not published until the early twentieth century.20M. Ferguson, The Printed Books in the Library of the Hunterian Museum (Glasgow: Jackson… , 1930); J. Young, A Catalogue of the Manuscripts in the Library of the Hunterian Museum (Glasgow: James Maclehose, 1908).

While the libraries of Sloane and Hunter were preserved largely intact, the French Revolution and its resulting social and economic upheaval put many great books on the market, causing what has been called the “golden age” of book collecting. A collector of books on sciences and the humanities who lived during this period of upheaval was the Italian neurologist Domenico Cotugno (1736-1822). Cotugno is represented in the Norman library both by his own writings (nos. 521-524) and by his copy of the first edition of Aselli (no. 76). Cotugno’s avocation as a bibliophile and humanist has been well described by Dorothy N. Schullian, who noted frequent references to the acquisition or examination of rare manuscripts and books in the published diaries of Cotugno’s travels.21D. N. Schullian, &ldquot;Domenico Cotugno as humanist,” in Essays on the History of Italian Neurology, ed. L. Belloni (Milan: Istituto di Storia della Medicina, 1963), pp. 67-74. Cotugno’s library covered medicine, surgery and the humanities, especially as reflected in editions of the classics. For example, we note that he acquired a set of the 1525 Aldine edition of Galen on a journey in 1765. Like other humanists of his time Cotugno was especially interested in the writings of the earliest medical historian, Celsus, and from examination of the 1828 auction catalogue of his library Schullian observed that Cotugno owned no fewer than twenty-four editions of Celsus, including the first edition of 1478 (see no. 424).

The career of Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (1752-1840), the Gottingen physician, anthropologist and polyhistor, also spanned the French Revolution and its aftermath. In 1840 his library of about 2,500 works was dispersed at auction, at which about 500 works, including some of the greatest treasures, were purchased by Blumenbach’s pupil and colleague, the physiologist E.F.G. Herbst (1803-1893). Most remarkably, this collection remained intact in the Herbst family until 1978 when I acquired it in Traverse City, Michigan, a small resort community sometimes called “The Cherry Capital of the World.” From an inscription in a seventeenth-century anatomical book in the Blumenbach/Herbst collection22Jeremy Norman & Co., Catalogue 6: Medicine, Travel & Anthropology from the Library of Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (San Francisco, 1979), no. 409. we know that Blumenbach was already collecting books at the age of fifteen. He acquired his first edition of Harvey’s masterpiece, Exercitatio anatomica de motu cordis (no. 1006) in 1774, when he was only twenty-two, and his annotations on the flyleaves indicate that he was fully aware of its rarity and bibliographical history. Blumenbach’s library is also represented in the Norman library by his first edition of Berengario da Carpi’s Commentaria … super anatomia Mundini (no. 187) and his copies of works by Volcher Coiter (nos. 496-497). Indisputably a bibliophile, Blumenbach also used his books as research tools. Among his numerous published works was one of the first subject bibliographies of medical historical literature, Introductio in historiam medicinae litterariam (1786).

Paralleling the rapid progress of science and technology in the mid-nineteenth century, we see the beginning here of the private collecting of books in the physical sciences as distinct from medicine. One of the first of these collectors was the mathematician and pioneer historian of mathematics, Augustus de Morgan (1806-1871), whose library of over 3,000 mathematical and scientific books is now in the University of London. An unusually prolific author, de Morgan contributed no less than 850 articles to the Penny Cyclopedia while writing regularly for about fifteen other periodicals. He also published numerous books, among them his Arithmetical Books from the Invention of Printing to the Present Time, being Brief Notices of a Large Number of Works Drawn up from Actual Inspection (London, 1847), which has been called the “first significant work of scientific bibliography.”23J. M. Dubby, “Augustus de Morgan,” in Dictionary of Scientific Biography IV (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1971), p. 36. The bulk of the work consisted of an extensively annotated list of treatises on arithmetic from 1491 to 1846, arranged in chronological order; de Morgan claimed that he had personally examined every book. Most of the books described were from de Morgan’s own library, which he acquired at relatively low cost because of the obscurity of the subjects involved. A few of the books he described came from the libraries of collector friends, and a few from the library of the British Museum. (At this early date the preparation of a catalogue of the British Museum Library was just beginning.) There is an index of 1,580 entries. A. N. L. Munby stated that “only in the physical descriptions of books cited is De Morgan’s great work disappointing.”24A. N. L. Munby, The History and Bibliography of Science in England: The First Phase, 1833-1845 (Berkeley: School of Librarianship; Los Angeles: School of Library Service, University of California, 1968), p. 11.

De Morgan was an eloquent exponent of the value of collecting the history of science. He wrote in his prefatory letter:

“The most worthless book of a bygone day is a record worthy of preservation. Like a telescopic star, its obscurity may render it unavailable for most purposes; but it serves, in hands which know how to use it, to determine the places of more important bodies.”25De Morgan, Arithmetical Books, p. ii.

Even though de Morgan’s library was not kept together when it was transferred to London University, his books were separately identified in the printed catalogue of London University Library published in 1876. Thus it is still possible to study one of the pioneering collections of books formed in England not just on mathematics, but on a wide range of the physical sciences.

A good friend of de Morgan and another pioneer exponent of the collecting of books in the physical sciences was Guglielmo Libri (1803-1869), as controversial a character as any in the history of bibliophily. A. N. L. Munby wrote, “So far as we know the notorious Libri, in his two great sales of 1861, was one of the first who set out to draw English collectors’ attention to works important in the history of thought. These two sales of books imported from France contain a magnificent series of manuscripts and books by Galileo, Copernicus, Kepler, Cardan, etc., many with long notes pointing out their significance, and we must not allow ourselves to be blinded to the showmanship and originality of Libri’s catalogue by his unenviable reputation as a forger and a thief. As in the case of T. J. Wise in our own day, Libri has fallen under a cloud which obscured his very real merits. The immediate financial results of these two sales must have been disappointing, but in them Libri gave an impetus to collecting in the scientific fields which was to culminate in the libraries of Young in the sphere of chemistry, of Osler and Cushing in medicine, and of [John Maynard] Keynes in philosophy and economics.”26A. N. L. Munby, “John Maynard Keynes: The book-collector,” in Essays and Papers (London: Scolar Press, 1977), pp. 20-21.

Guglielmo Bruto Icilio Timoleone, Conte Libri Carucci della Sommaia, was born in Florence in 1803, studied law and natural science, and at the age of twenty held a chair in mathematics at Pisa. He moved to France as a political refugee in 1830 and was naturalized in 1833, being elected a member of the Institut and receiving appointment to a professorship of mathematics at the Sorbonne. From 1838 to 1841 he published the well-respected four-volume Histoire des sciences mathématiques en Italie, depuis la rénaissanace des lettres jusqu’… la fin du dix-septième siècle. He planned to complete this work in a total of six volumes, but never finished the task. Libri considered the mathematical sciences to encompass what we would call the exact sciences today, including astronomy and physics; the last volume of his Histoire is almost entirely devoted to Galileo. On the basis of this work Libri must be considered one of the pioneer historians of science. According to Munby,27A. N. L. Munby, “The earl and the thief,” in Essays & Papers, pp. 176ff. Libri also showed great aptitude for bibliography and paleography, and started to form a large library. As early as 1835 he was also dealing in printed books and manuscripts. Within ten years he had built up a significant antiquarian book business, building large collections which were chiefly dispersed at auction. Brunet cautioned that Libri’s catalogue descriptions tended to exaggerate the value of the books described.

Combative by nature, Libri also plunged himself into political and learned controversy in France just as he had in Italy, eventually antagonizing half of the Académie des Sciences. A particularly vicious animosity developed between him and the influential François Arago, perpetual secretary of the Académie (see no. 1594). In spite of his political problems Libri somehow succeeded in having himself appointed secretary of a new commission set up to oversee the publication of a union catalogue of manuscripts in French public libraries. It was in this official capacity that Libri toured the libraries of France, clad in a capacious cloak and armed with a stiletto, which he claimed to need as protection from his Italian political enemies. With unlimited access to all of the greatest treasures of the French provincial public libraries, Libri plundered numerous illuminated manuscripts, including biblical texts of great antiquity. Later he employed forgers to alter provenances or bindings to imply that some of the plundered manuscripts had originated in Italy rather than in France.

Between 1835 and 1846 Libri proceeded to consign various portions of his stock of printed books to the French auction rooms. By 1845 he decided to offer his manuscripts for sale abroad, doubtless because of the questionable provenance of many items. His friendship with his fellow countryman and political exile Anthony Panizzi, librarian of the British Museum, led him initially to offer his manuscript treasures to that institution. In spite of widely expressed doubts about Libri’s legal title to some of the manuscripts, Libri succeeded in selling the collection for £8,000 to Bertram, fourth Earl of Ashburnham, in 1847. The increasing heat of scandal made it expedient for him to emigrate to England with the manuscripts. In 1850 the French tried him in absentia and sentenced him to ten years of solitary confinement with hard labor. Nevertheless, confusion over Libri’s guilt or innocence and the aggressive loyalty of his influential friends like de Morgan and Panizzi, aggravated by mutual animosity between the French and English in the so-called “Affair Libri,” resulted in Libri’s vindication in England; however, he was never able to return to France. The history of this remarkable controversy and its resultant pamphlet literature has been ably studied by Munby and others.

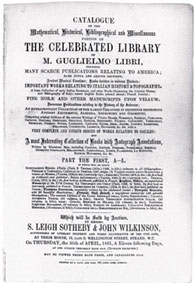

Notwithstanding the undoubtedly questionable provenance of many books in Libri’s sales of 1861, his catalogue contains, among its 7,628 lots sold over 20 days, the first large collection on the history of science to appear at auction.28G. Libri, Catalogue of the Mathematical, Historical, Bibliographical and Miscellaneous Portion of the Celebrated Library of M. Guglielmo Libri … (London: S. Leigh Sotheby & John Wilkinson). Part I: 25 April 1861 and 11 following days; Part II: 18 July 1861 and 7 following days. The catalogue is also notable for its thirty-page introduction by Libri, published in both English and French on facing pages. Writing 130 years ago, Libri expressed a strikingly modern rationale for the history of science:

"The Collection about to be sold is composed for the most part of Books relative to the Sciences (more particularly mathematics), and their History, taken in its most extended sense, that is to say, comprising also many works of biography, bibliography, literary history, and even general literature, necessary to shed light on the march of the human mind… . independently of a design for immediate and practical utility, he, who wishes to apply his mind to the study of the progress of human knowledge, ought to propose to himself a problem of a higher order. He ought, in attentively examining the road pursued by inventors, to endeavour to discover, track by track, at least as far as is permitted, their method of arriving at such invention. To neglect the path by which human nature ought to have passed to arrive at such or such a discovery,--for example, not to stop at a mathematical theorem, until at the hands of a Lagrange or a Gauss it has received a definitive form,--would be to act as a naturalist who attempted only to study insects under the shape of beautiful butterfiles, without giving the slightest attention to the caterpillars, to those less perfect larvae which at a later period are to be transformed into those self-same lepidoptera… . What has already been so suitably done for literary history will eventually be carried out, having already been commenced, for the history of sciences. Solely for the reason that there are more persons who read Shakespeare or Dante than there are those who understand Copernicus or Fermat, it becomes manifest why the interest attached to what may be termed “Curiosities of Literature” is more common, and far wider spread, than that which is excited by books, such as form simply an epoch in the history of science."

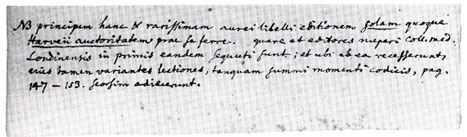

According to Blumenbach’s manuscript note in his own copy, the first edition of Harvey’s De motu cordis (1628) was already of the greatest rarity by the end of the eighteenth century.

According to Blumenbach’s manuscript note in his own copy, the first edition of Harvey’s De motu cordis (1628) was already of the greatest rarity by the end of the eighteenth century.

The verbose title page (top) of Sotheby’s auction catalogue summarizes the highlights of Libri’s science library. Libri’s catalogue annotations (bottom), written in 1861, resemble some of those found in antiquarian booksellers’ catalogues today.

The verbose title page (top) of Sotheby’s auction catalogue summarizes the highlights of Libri’s science library. Libri’s catalogue annotations (bottom), written in 1861, resemble some of those found in antiquarian booksellers’ catalogues today.To reconstruct the lives of the great scientists, Libri believed in collecting all of their writings, and his auction catalogue contains extensive runs of first editions by such authors as Galileo and Stensen. He also had numerous important association copies and manuscripts. Libri pointed out in his introduction that while the catalogue descriptions were mainly written by auction house cataloguers, he himself was responsible for the informative notes appended to many catalogue entries.

In the fifth and final edition of his Manuel du libraire (1860-1865), the Parisian bookseller and bibliographer Jacques Charles Brunet (1780-1867) noted the unusual value of Libri’s “mathematical” auction catalogue, but pointed out the difficulties and advantages of using a catalogue arranged partly by author and partly by subject. Nowhere in his notes on Libri’s catalogues did Brunet refer to Libri’s unsavory reputation, which must been notorious in the French book trade.

Brunet’s Manuel has been called by Breslauer and Folter, “the best and last of the general rare book bibliographies… . Brunet’s annotations about the scholarly and commercial value of the books he listed are often still unsurpassed. There is hardly any other bibliography in which the wide range of its author’s knowledge is more favorably displayed.”29Breslauer & Folter, no. 118. Brunet’s work is still of great practical utility for antiquarian booksellers and collectors of early books in all subjects. It listed 32,000 titles, many with informative notes and even prices. In his introduction Brunet described the trends in book collecting which were popular in his time. Regarding scientific books, of which he listed 5,700 titles, Brunet suggested that books recording important discoveries or expressing the great ideas should be collected. He personally preferred fine natural history books of the eighteenth century, medicine and surgery of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, and, not unlike Libri, he recommended Italian, French, and German mathematics of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

Although we do not know of any booksellers who specialized in the history of science and medicine during the second half of the nineteenth century, the book trade was growing in sophistication, and the collecting of rare books and manuscripts on many subjects was becoming a very fashionable pursuit. Reflecting this appeal, the great book collecting clubs began to be formed, including the French Société des Amis du Livre, founded in 1876, and the Grolier Club of New York, founded in 1884. The first club of this type, the celebrated Roxburghe Club, was formed in England in 1812.

Despite the increasing interest in antiquarian books, very few of the libraries of nineteenth-century scientists cited by Wells seem to have been notably antiquarian or bibliophilic in nature, although many undoubtedly contained some a few antiquarian volumes. One scientist who could certainly have afforded to collect antiquarian books was Charles Darwin--however, far from being a book collector, Darwin was what we have an example of what I would call an anti-bibliophile! Francis Darwin pointed out, in his introduction to the published catalogue of his father’s library of 1,750 volumes,30F. Darwin, “Introduction,” in H. W. Rutherford, Catalogue of the library of Charles Darwin now in the Botany School, Cambridge (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1908). Darwin’s more than casual attitude to his books also meant that he did not hesitate to write in them, and this has increased their research value for scholars. A few of Darwin’s books with his notes escaped the donation to Cambridge and have appeared on the market during the past twenty years. that Darwin’s books tended to be in poor condition because he “hardly ever had a book bound… . The rough treatment he gave his books is described in the Life and Letters: an example may be seen in the sixth edition of Lyell’s Elements [of geology] which he found too heavy to be read with comfort, and converted into two volumes by cutting in half.” (p. viii). Darwin also had the habit of extracting articles he wished to save from journals and discarding the rest; sometimes he even applied this space-saving principle to sections of books. Fortunately Darwin owned no fine or particularly beautiful books that he could destroy that way. The only volume in his library published prior to the nineteenth century was a copy of Sprengel on the fertilization of flowers (see no. 1990), which he purchased in 1841 on the advice of Robert Brown (see no. 353). It is well known that Sprengel’s work stimulated Darwin’s extensive interest in this subject.

Another one of Darwin’s bookish eccentricities was his dislike of having to cut the unopened pages of books. For this reason, he ordered a few special trimmed copies of nearly all of his later publications to use as presentation copies. These special presentation copies are shorter, and their cloth bindings had to be modified slightly to fit the smaller book block. See no. 600 for one of these special copies.

One of the few nineteenth-century pioneers in the collecting of antiquarian scientific books was Latimer Clark (1822-1898), an electrical engineer and inventor who, in partnership with Sir Charles Tilson Bright, was responsible for laying many of the first submarine telegraphic cables. While pursuing a remarkably successful and creative scientific and entrepeneurial career, Clark also found time to build the most complete collection ever formed of early books and manuscripts on the history of electricity and magnetism. After his death it was purchased by the American engineer, Schuyler Skaats Wheeler (1860-1923) and donated by him to the American Institute of Electrical Engineers in New York. The extensively annotated and illustrated catalogue of the collection of 5,966 items, in two volumes edited by William D. Weaver, with introduction and extensive annotations by Brother Potamian and financed by Andrew Carnegie, is still of great bibliographic value. It is usually cited as the “Wheeler Gift” collection.31W. D. Weaver, ed., Catalogue of the Wheeler Gift of Books, Pamphlets, and Periodicals in the Library of the American Institute of Engineers. With introduction, descriptive and critical notes by Brother Potamian (New York: American Institute of Electrical Engineers, 1909).

The other great nineteenth century pioneer of specialist science collecting was the chemist James Young (1811-1883), an assistant to Thomas Graham, who became one of the earliest technical chemists. Young’s discovery of the distillation of paraffin from coal and oil-shales made him the founder of the Scottish shale oil industry. In about 1850, Young set out to collect the classic original works in the history of alchemy and chemistry, eventually aided in this pursuit by the pioneer historian and bibliographer of chemistry, Dr. John Ferguson (1837-1916), professor of chemistry in the University of Glasgow from 1874-1915.32E. H. Alexander, A Bibliography of John Ferguson … Reprinted, with Alterations, from the Transactions of the Glasgow Bibliographical Society ([Glasgow: n.p.] 1920); A Further Bibliography of the Late John Ferguson … Reprinted with Alterations, from the Records of the Glasgow Bibliographical Society ([Glasgow: n.p.] 1934). The Young collection eventually numbered about 1,400 separate items, many of which were already of the greatest rarity by the end of the nineteenth century. The resultant catalogue, prepared by Ferguson and issued in two volumes from Glasgow in 1906, contains more than a thousand densely printed quarto pages.33J. Ferguson, Bibliotheca chemica: A Catalogue of the Alchemical, Chemical and Pharmaceutical Books in the Collection of the Late James Young of Kelly and Durris… (Glasgow: James Maclehose, 1906). It is one of the great landmarks of descriptive scientific bibliography. With its bibliographical details of each work, biographical notices of each writer, and exhaustive lists of references in chronological order, its scope and accuracy have set a standard rarely equalled for the bibliography of the history of science. While some of Ferguson’s scholarship has been superseded, Sir William Osler considered Ferguson’s catalogue the model of descriptive scientific bibliography. The Young collection is now in the Andersonian Library, University of Strathclyde, Glasgow.

What is generally forgotten is that John Ferguson also was a pioneering collector in the history of alchemy and early chemistry and that his collection is in some respects more extensive than the Young collection. The main reason that the Ferguson collection at the University of Glasgow Library is so little known is that its catalogue was never published in the official sense. Only forty sets of the catalogue (not annotated) were printed for distribution to academic libraries during World War II. A very few sets of page proofs, printed on one side of the sheet only, were also made available at a later date.34W. R. Cunningham, Catalogue of the Ferguson Collection of Books Mainly Relating to Alchemy, Chemistry, Witchcraft and Gypsies (Glasgow: Robert Maclehose, 1943).

Only two years after the publication of Ferguson’s catalogue of the Young collection, David Eugene Smith, a historian of mathematics, published Rara arithmetica, the catalogue of the collection of arithmetical books formed in the latter half of the nineteenth century by George Arthur Plimpton of New York. Inspired by de Morgan, and probably incorporating some volumes from Libri’s auctions, Plimpton’s library of arithmetical books and manuscripts printed before 1700 was the finest ever formed. It may also have been the first specialized private collection of scientific antiquarian books formed by an American for which we have a bibliographical catalogue. When Plimpton died in 1936 he bequeathed his library to Columbia University. In 1939 Smith published a 52-page addenda to Rara arithmetica recording Plimpton’s final additions to the library.35D. E. Smith, Rara arithmetica. A Catalogue of the Arithmetics Written Before the Year MDCI with a Description of Those in the Library of George Arthur Plimpton (Boston: Ginn & Co., 1908); Addenda to Rara arithmetica (Boston: Ginn & Co., 1939). Other notable early American scientific libraries were those of Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) and Nathaniel Bowditch (1773-1838). At his death Franklin possessed 4,276 volumes which were dispersed by bequest, sale, and auction. Many of these are preserved in American libraries and Edwin Wolf 2nd attempted a reconstruction; see Wolf, E. “The reconstruction of Benjamin Franklin’s library: an unorthodox jigsaw puzzle,” Papers Bib. Soc. Amer. 56 (1962), pp. 1-16. Bowditch’s library of 2,500 volumes, containing many rare astronomical works and several of his own manuscripts, is preserved in the Boston Public Library.

In 1906, the year that Ferguson published his catalogue of the Young collection, Heinrich Zeitlinger began issuing his encyclopedic rare book catalogues of classics in the history of science, as distinct from medicine, for the London firm of Henry Sotheran and Co. The first series of these catalogues, entitled Bibliotheca chemico-mathematica: Catalogue of Works in Many Tongues on Exact and Applied Science, with a Subject-Index, Compiled and Annotated by H. Z., and H. C. S., was issued in 1921; the introduction stated that it was “perhaps, the first Historical Catalogue of Science published in any country, at least as giving at once the current price of each book included, bibliographical particulars, and many biographical and historical references both in the descriptions themselves and in the notes.” Altogether the catalogue extended to two volumes plus three supplements in four additional volumes, ending in 1956. While other English antiquarian bookselling firms such as Maggs Bros. and Bernard Quaritch Ltd. occasionally issued catalogues on the history of science and medicine during the 1920s, the firm of Sotheran, with Zeitlinger as its resident expert, held a leading position in the English trade in history of science books up to the end of World War II. By the 1950s the firm was no longer pre-eminent, having been eclipsed by Ernst Weil, Dawsons of Pall Mall, E.P. Goldschmidt and others. Nevertheless, its series of catalogues and supplements represents the most complete priced record of the values of rare scientific books from 1906 to 1956. Taken together it is probably the most comprehensive set of catalogues of rare scientific books ever issued by a single bookseller.

The collector most responsible for stimulating the development of collecting both science and medicine was Sir William Osler (1849-1919). Osler was above all an inspirational teacher and writer, stimulating many of his students to follow his example as both an exemplary medical practitioner and a collector of books. Osler was the watershed figure in this collecting field; from him the line runs uninterrupted right to the present. Osler was also a generous supporter of libraries, frequently donating important books to encourage the development of history of medicine collections. Osler had a very hard time resisting the first edition of Vesalius’s Fabrica (1543) whenever he found one available. In 1903 he bought three copies, saying it was not a book that should ever be left on the shelves of a bookseller, and he sent one copy to McGill University. Six years later, when in Rome, he sent another copy to the same library. He is also known to have attempted to present a second copy to the Boston Medical Library a few years after he first presented a copy to that institution. The Boston librarian refused Osler’s second gift but the volume found a place at the New York Academy of Medicine! This reckless generosity sometimes left Osler so short of money when abroad that he had difficulty in paying his fare for the return home. Altogether Osler presented six copies of the Fabrica to libraries and other copies to students such as Harvey Cushing.

Through his prolific writings Osler reached a wide-ranging audience in America and England. The catalogue of his library preserved at McGill University, the Bibliotheca Osleriana (1929; no. 1618) has been consulted by virtually every collector and bibliographer of rare books in the history of medicine since it was published, including my father, who became closely familiar with it over the years.36Some of the most interesting and informative articles on Osler as a book collector, including Ellen Wells’s study of Osler’s book bills, are found in Appendix A to R. L. Golden & C. G. Roland’s Sir William Osler: An Annotated Bibliography with Illustrations (San Francisco, Norman Publishing, 1988). That work also contains an appendix on Osler’s outstanding sense of humor! Volumes from Osler’s personal library in this collection include nos. 1078, 1128 and 2155. Also included is one of the four interleaved copies of the Bibliotheca Osleriana bound in two volumes (no. 1619).

Cushing republished Osler’s address in the United States. In the frontispiece Osler is shown holding the Stirling-Maxwell copy of Vesalius’s Tabulae anatomicae sex, now in the Hunterian collection at the University of Glasgow Library.

Cushing republished Osler’s address in the United States. In the frontispiece Osler is shown holding the Stirling-Maxwell copy of Vesalius’s Tabulae anatomicae sex, now in the Hunterian collection at the University of Glasgow Library.

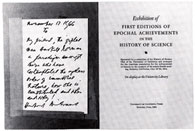

This small broadside to accompany Osler’s exhibition of twenty epochal works represents one of the first (if not the first) collectors’ lists of so-called “high-spots” in the history of science and medicine. Photos courtesy of the Osler LIbrary, McGill University.

What has generally been forgotten is that Osler collected landmarks in the history of science and well as medicine. To accompany his now-famous address on The old humanities and the new science in 1919, Osler set out a special exhibition of twenty works from his library covering the development of science and medicine from Plato to Newton. The arrangement of the exhibit previewed his concept and selection of the Bibliotheca prima later fully developed in the Bibliotheca Osleriana.

In planning the Bibliotheca Osleriana, Osler was particularly influenced by Ferguson’s Bibliotheca chemica. In a tribute to Ferguson’s memory, Osler stated that “though an absorbing and profitable study, the results of bibliography are too often recorded in tomes of intolerable dullness. The merit that appeals to me is the combination of biography with bibliography. Beside the book is a picture of the man sketched by a sympathetic hand.”37Golden & Roland, no. 1044. From this we might conclude that the annotations in the Bibliotheca Osleriana would have been much fuller if Osler had lived to see the work completed.

During the last fourteen years of Osler’s life at Oxford, the young Geoffrey Keynes (1887-1982) felt privileged to be his friend. Best known as the author of many scholarly works on such writers as John Donne and William Blake, and for his definitive bibliographies of Sir Thomas Browne, John Evelyn, William Harvey, Robert Hooke, Martin Lister, John Ray, etc. (many of which were used in the compilation of this catalogue), Keynes was by profession a general surgeon, and was knighted for his contributions to medicine. He was also the younger brother of another book collector, the economist John Maynard Keynes. Geoffrey Keynes pursued his bibliographical and scholarly career in tandem with medicine throughout his life, and had the advantage of living very productively for 30 years after his retirement from medicine at the age of 65. His literary output during this “second career” was truly remarkable.

Keynes’s friendship with Osler, which began with a mutual interest in Sir Thomas Browne, clearly influenced his entire life. In his autobiography, The Gates of Memory (1981), much of which is concerned with his bibliophilic and biliographic activities, Keynes described the importance of his friendship with Osler on his development as a physician, scholar and book collector. Significantly, he also ended the autobiography by reprinting his essay, “The Oslerian tradition,” allowing the reader to draw the obvious parallels between Osler’s life and his own.

As a book collector Keynes concentrated primarily on books by certain authors, building numerous small collections as source material for his bibliographies. His library of 4,316 items, most of which do not concern science or medicine, was described in Bibliotheca bibliographici (1964). Because of the wide range of his scholarship Keynes’s influence on the collecting of books in science and medicine was chiefly through his many bibliographies, which stimulated the interests of many collectors in the authors Keynes studied.

The neurosurgeon Harvey Cushing (1869-1939) also received his inspiration directly from William Osler and proceeded to build a library which in some ways is more interesting than Osler’s to today’s collector, though this is difficult to discern from its highly abbreviated unannotated catalogue38The Harvey Cushing collection of books and manuscripts (New York: Schuman’s, 1943).. The close friendship between Osler and Cushing is all the more remarkable in that they were so different in temperament, Osler being generally up-beat, congenial and much-beloved, with a weakness for practical joking, and Cushing being difficult and iron-willed, tending to inspire respect rather than win friends. Golden and Roland’s bibliography of Osler reproduces documents showing how Cushing and Osler often cooperated on book purchases. Like Osler, Cushing collected the history of science as well as medicine. Hidden in the catalogue of Cushing’s library one finds more classics in the history of science than in the Bibliotheca Osleriana. While my father frequently consulted the catalogue of Cushing’s library to check Cushing’s holdings, he was more influenced by Cushing’s Bio-Bibliography of Andreas Vesalius (1943) and by Cushing’s account of Osler in his Pulitzer Prize-winning biography (no. 552). The Norman library contains two volumes from Cushing’s personal library (nos. 1822 and 2063), various works he presented as gifts, and a selection of original editions of Cushing’s writings.

Herbert M. Evans

Herbert M. Evans  Evans’s inscription to my father illustrates his propensities for both eloquence and flattery. Borrowing from Evans’s favorite quotation from Euripides, it reads: “To my friend, the gifted man, Haskell Norman, a paradigm amongst those who have contemplated the ageless order of immortal nature, how she is constituted and when and why!”

Evans’s inscription to my father illustrates his propensities for both eloquence and flattery. Borrowing from Evans’s favorite quotation from Euripides, it reads: “To my friend, the gifted man, Haskell Norman, a paradigm amongst those who have contemplated the ageless order of immortal nature, how she is constituted and when and why!”Probably the most interesting of the Cushing first editions in the Norman library is the copy of Cushing’s book on the pituitary, presented, with an eloquent inscription, to his intellectual successor in that field, Herbert McLean Evans (no. 549). A student of Cushing’s at Johns Hopkins, Evans (1882-1971) stated that he had been inspired to collect the history of science and medicine by hearing Osler deliver a speech on Michael Servetus at the Johns Hopkins Historical Club in 1909.39Golden & Roland, no. 984. Evans went on to build numerous collections on the history of science and medicine, none of which ever had an appropriate bibliographical catalogue. Nevertheless, Evans had a profound influence on this collecting field through the wide placement of his collections sold to institutions across the United States, further stimulating the collection of rare books in the history of science and medicine. This is more fully discussed in my father’s introduction.

Evans was also highly influential on other collectors with his publication of the first list of “high-spots” in the history of science, an annotated pamphlet appropriately entitled Exhibition of First Editions of Epochal Achievements in the History of Science (no. 743), describing an exhibition of his books and books from the University Library which he mounted at the University of California at Berkeley in June, 1934. Prepared before the existence of other guides of its type, this small pamphlet had notable influence on later American collectors in this field, and the later guides that built upon it such as Dibner’s Heralds of Science (1955; rev. ed. 1980), Horblit’s One Hundred Books Famous in Science (1964), and even on some of the scientific and medical selections in that wide-ranging selection of books which influenced Western civilization, Printing and the Mind of Man (1967). Some of Evans’s original selections may also be found in that most recent and most splendid incarnation of a list of bibliophilic high-spots in the history of thought issued by the Bibliothèque Nationale -- En francais dans le texte. Dix siecles de lumières par le livre (1990).40Cited as “E.F.D.T.” in our catalogue, this work is an illustrated and enhanced development of the “Printing and mind of man” concept as applied to works in the French language.

With characteristic eloquence Evans prefixed his introduction to his catalogue with a quotation from Euripides:

“Blessed is he who contemplates the ageless order of immortal nature, how it is constituted and when and why.”

Evans then wrote, “No single feature of man’s past equals in importance his attempt to understand the forces of Nature and himself. It is a safe prediction that the historian of the future will be concerned increasingly with the chronicle of the intellectual acquisitions of man, for this deeper story includes not merely improvement in material comforts but mental enlargement which transcends every other feature of human evolution.”

Besides books presented from Cushing to Evans (no. 322, etc.) Evans is represented in the Norman library by several of his own writings, by a wide variety of books from one or another of his collections, and by numerous books from Evans’s personal library purchased from John Howell--Books after Evans’s death. They may be located via the provenance index. Through personal contact over several years Evans had a profound influence on both my father and myself.

The leading European collector of medicine and allied sciences during the collecting careers of both Cushing and Evans was the Swedish gastric surgeon, Erik Waller (1875-1955) who built a magnificent library of 21,000 volumes works from during the four decades from 1910 to 1950. Based in Europe, he frequently could pre-empt Cushing on books of mutual interest by being closer to the source. The Waller collection is virtually definitive for the history of European medicine, surgery, and dentistry, often containing books not in the catalogues of the libraries of other private collectors or institutions. Waller’s collection of original editions of the writings of Ambroise Paré may be the largest of all collections of this author. His collection of Paracelsus is also outstanding. The two-volume catalogue of the Bibliotheca Walleriana prepared by Hans Sallander briefly describes the books without any annotations. It does, however, include paginations, and it illustrates the title pages of some remarkable rarities and association copies, including one of the few known books from Vesalius’s personal library.41Apparently acquired by Waller for £5 because the collector F. J. Cole could not afford it. See N. B. Eyles, “On the provenance of some early medical and biological books,” J. Hist. Med. 24 (1969), pp. 183-192. For an account of some of the other remarkable association copies in the Waller library see H. Sallander, “The Bibliotheca Walleriana in the Uppsala University Library,” Nordisk tidskrift för bok- och biblioteksväsen 38 (1951) pp. 49-74. Sallander remarked that Waller collected his library at “a time when competition on the old and rare book market was running high”. It does not describe Waller’s vast collection of 20,000 medical autographs and manuscripts, which is also preserved at the University of Uppsala. 2,100 copies of this bibliography were printed, a very large edition for such a specialized work. Issued in 1955, it remained in print until about 1980.

Both Cushing and Waller had the great advantage of collecting books between the two World Wars. The social upheaval caused by World War I caused the dispersal of many great European libraries, and economic conditions during the great depression of the 1930s also made many books available at low prices. Some of the most notable and useful annotated bookseller’s catalogues of rare medical books issued between the two World Wars were those of l’Art Ancien, from Lugano and later from Zurich. One entitled Early Books on Medicine, Natural sciences, and Alchemy, issued between 1926-1928, described on 715 pages 988 items printed between 1488 and 1800 with full descriptions and many illustrations. It contains a complete subject index. A few years later l’Art Ancien’s catalogue 21, Bibliotheca Medica, appeared, dedicated to Harvey Cushing, “one of the greatest figures in the history of medicine and one of its best connoiseurs” (presumably Cushing was one of l’Art Ancien’s best customers). The catalogue described 900 books from Hippocrates to Freud.

In 1929 Maggs Bros. of London issued a great catalogue entitled Medicine, Alchemy, Astrology & Natural sciences (cat. 520). This described 1,252 rare books, manuscripts, and prints on 618 pages, in chronological order but with complete author and subject indices. The firm of R. Lier & Co. in Milano, antiquarian booksellers and publishers, issued from 1932 to 1932 a most remarkable series of sixteen catalogues entitled Early Medical Books, which reflect the availability of the choicest early rarities during this period.

The social upheaval caused by World War II may have been even more widespread than that caused by World War I. It was also highly disruptive of the antiquarian book trade, forcing many Jewish booksellers to emigrate, and the overall international trade was greatly curtailed. The German bookseller Ernst Weil emigrated to London where he worked for a time with E. P. Goldschmidt before establishing his own business, specializing exclusively in science and medicine. Weil issued his first catalogue in 1943; it was followed by thirty-two others, the last appearing just before his death in 1965. He combined a wide range of scholarship in the history of science and medicine with excellent and imaginative taste. His catalogues remain extremely useful today. In his introduction my father has discussed Weil’s crucial role in the formation the Norman library.

One of the most outstanding collectors of scientific books from the 1930s through the 1950s was the English chemist, Denis I. Duveen (1910- ). A relative of the great art dealer, Joseph Duveen, Denis Duveen was inspired to collect by a chance visit to Heinrich Zeitlinger of Henry Sotheran & Co. He set about to form a library on the model of the Young collection as catalogued by Ferguson. Living in Paris during the 1930s, Duveen built up his library of alchemy and early chemistry chiefly with the help of Zeitlinger and Emil Offenbacher, and later Ernst Weil and Lucien Scheler.42D. I. Duveen, “The Duveen alchemical and chemical collection,” The Book Collector 5 (1956), pp. 331-342.

During this period of general availability of books Duveen was able to form his library of about 3,000 volumes, including the greatest rarities in alchemy and chemistry, in only fifteen years. The annotated catalogue of Duveen’s library, entitled Bibliotheca alchemica et chemica, was published by E. Weil in 1949. The first edition of this work was issued in only 200 copies and has become particularly scarce; however, it was never copyrighted and there have been two reprints since. It was a highly useful reference for selecting chemical books in the Norman library. Although the title page implies that the catalogue was written by Duveen himself, it was actually mostly written by Herbert S. Klickstein, a physician and historian of chemistry.